Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To determine whether managed care is associated with reduced access to mental health specialists and worse outcomes among primary care patients with depressive symptoms.

DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

SETTING: Offices of 261 primary physicians in private practice in Seattle.

PATIENTS: Patients (N=17,187) were screened in waiting rooms, enrolling 1,336 adults with depressive symptoms. Patients (n=942) completed follow-up surveys at 1, 3, and 6 months.

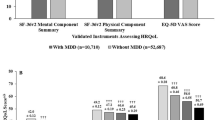

MEASUREMENTS AND RESULTS: For each patient, the intensity of managed care was measured by the managedness of the patient’s health plan, plan benefit indexes, presence or absence of a mental health carve-out, intensity of managed care in the patient’s primary care office, physician financial incentives, and whether the physician read or used depression guidelines. Access measures were referral and actually seeing a mental health specialist. Outcomes were the Symptom Checklist for Depression, restricted activity days, and patient rating of care from primary physician. Approximately 23% of patients were referred to mental health specialists, and 38% saw a mental health specialist with or without referral. Managed care generally was not associated with a reduced likelihood of referral or seeing a mental health specialist. Patients in more-managed plans were less likely to be referred to a psychiatrist. Among low-income patients, a physician financial withhold for referral was associated with fewer mental health referrals. A physician productivity bonus was associated with greater access to mental health specialists. Depressive symptom and restricted activity day outcomes in more-managed health plans and offices were similar to or better than less-managed settings. Patients in more-managed offices had lower ratings of care from their primary physicians.

CONCLUSIONS: The intensity of managed care was generally not associated with access to mental health specialists. The small number of managed care strategies associated with reduced access were offset by other strategies associated with increased access. Consequently, no adverse health outcomes were detected, but lower patient ratings of care provided by their primary physicians were found.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405–18.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31.

Ginzberg E. Managed care and the competitive market in health care: what they can and cannot do. JAMA. 1997;277:1812–3.

Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS. Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996.

Schulberg HC, Katon WJ, Simon GE, Rush AJ. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1121–7.

Schulberg HC, Katon WJ, Simon GE, Rush AJ. Best clinical practice: guidelines for managing major depression in primary medical care. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 7):19S-26S.

Rogers WH, Wells BK, Meredith LS, Sturm R, Burnam A. Outcomes for adult outpatients with depression under prepaid or fee-for-service financing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:517–25.

Grembowski DE, Cook K, Patrick DL, Roussel AE. Managed care and physician referral. Med Care Res Rev. 1998;55:3–31.

Kassirer JP. Access to specialty care. New Engl J Med. 1994;331:1151–3.

Grembowski D, Diehr P, Novak LC, et al. Measuring the managedness and covered benefits of health plans. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:707–34.

Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P, ed. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. Basel, Switzerland: Kargerman; 1974;79–110.

Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, LeResche L, Kruger A. An epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints. Pain. 1988;32:173–83.

Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. The predictors of persistence of depression in primary care. J Affect Disord. 1994;31:81–90.

Goldberg HI, Wagner EH, Fihn SD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of CQI teams and academic detailing: can they alter compliance with guidelines? Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:130–42.

Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR. Differences in 4-year health outcomes for elderly and poor, chronically ill patients treated in HMO and fee-for-service systems: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1996;276:1039–47.

Hays RD, Shaul JA, Williams SL, et al. Psychometric properties of the CAHPS 1.0 survey measures. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37:22–31.

Frank RG, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP. Some economics of mental health ‘carve-outs.’ Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:933–7.

Rush AJ, Golden WE, Hall GW, et al. Depression in Primary Care, Vol 1 and 2: Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5. AHCPR Publication No. 93-0551. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1993.

Wells KB, Rogers W, Burnam MA, Greenfield S, Ware JE Jr. How the medical comorbidity of depressed patients differs across health care settings: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1688–96.

Brach C, Sanches L, Young D, et al. Wrestling with typology: penetrating the “black box” of managed care by focusing on health care system characteristics. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 2):93S-115S.

Forrest CB, Glade GB, Starfield B, Baker AD, Kang M, Reid RJ. Gatekeeping and referral of children and adolescents to specialty care. Pediatrics. 1999;104:28–34.

Wells KB, Burnam A, Rogers W, Hays R, Camp P. The course of depression in adult outpatients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:788–94.

Ware JE, Brook RH, Rogers WH, et al. Comparison of health outcomes at a health maintenance organization with those of fee-for-service. Lancet. 1986;1:1017–22.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score (in applications). J Am Statistical Assoc. 1984;79:516–24.

Norquist GS, Wells KB. How do HMOs reduce outpatient mental health care costs? Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:96–101.

Liu X, Sturm R, Cuffel BJ. The impact of prior authorization on outpatient utilization in managed behavioral health plans. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:182–95.

Grazier KL, Pollack H. Translating behavioral health services research into benefits policy. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:53–71.

Sturm R, Meredith LS, Wells KB. Provider choice and continuity for the treatment of depression. Med Care. 1996;34:723–34.

Scheffler R, Ivey SL. Mental health staffing in managed care organizations: a case study. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1303–8.

Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–50.

Scott RA, Aiken LH, Mechanic D, Moravcsik J. Organizational aspects of care. Milbank Q. 1995;73:77–95.

Wells KB, Manning WG, Valdez RB. The effects of insurance generosity on the psychological distress and psychological well-being of a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:315–20.

Newhouse JP and the Insurance Experiment Group. Free For All? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1993.

Sturm R, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, et al. Mental health utilization in prepaid and fee-for-service plans among depressed patients in the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:319–40.

Sturm R, Klap R. Use of psychiatrists, psychologists, and master’s-level therapists in managed behavioral health care carve-out plans. Psychiat Serv. 1999;50:504–8.

Dudley RA, Miller RH, Korenbrot TY, Luft HS. The impact of financial incentives on quality of care. Milbank Q. 1998;76:649–86.

Kerr EA, Mittman BS, Hays RD, et al. Managed care and capitation in California: how do physicians at financial risk control their own utilization? Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:500–4.

Mulrow C, Williams J Jr, Gerety M, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Am Coll Physicians. 1995;122:913–21.

Hough R, Landsverk J, Stone J, et al. Comparison of Psychiatric Screening Questionnaires for Primary Care Patients. Final report for NIMH Contract #278-81-0036. Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Mental Health; 1983.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funding support was received from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (formerly AHCPR) Grant No. HS06833.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grembowski, D.E., Martin, D., Patrick, D.L. et al. Managed care, access to mental health specialists, and outcomes among primary care patients with depressive symptoms. J GEN INTERN MED 17, 258–269 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10321.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10321.x